Documentary films combine the visual power of a cinematic narrative with the journalistic integrity expected from a reliable news source. Documentaries can not only make viewers feel new emotions and challenge old ideas, they can also record a moment in time.

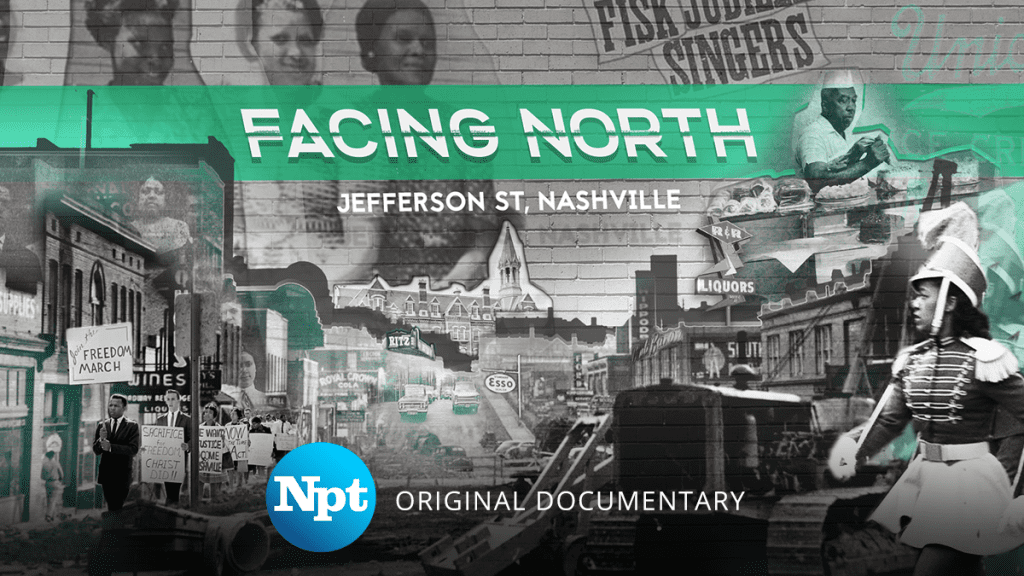

Wanting to capture the essence of a historic black community, the Nashville Public Television (NPT) documentary “Facing North: Jefferson Street, Nashville” covers the extraordinary history and cultural contributions the district has brought to both Music City and the world.

The documentary is produced by NPT’s Producer-Reporter LaTonya Turner, who works for the station to develop programming that is relevant for Nashville’s airwaves. Sifting through hours of interviews with residents of the Jefferson Street area and community historians, LaTonya has stitched together a composite story of Jefferson Street. The narrative covers several decades of the area’s past, resulting in a sweeping study of this particular part of the city between the 1940s and 1960s.

LaTonya says that though there’s been some reporting done on the music and entertainment generated by the area, she was eager to tell the whole story of Jefferson Street—partly because it’s a story that hasn’t been told. She tells Launch Engine, “Being an African-American woman who was born and raised in the South, [I am] somewhat familiar with how historic black communities have been disregarded, neglected, [or] omitted from historical accounts. … In many ways, [they] have been sort of battered or bruised by a number of things—including urban renewal, neglect by municipal governments, or targeting by municipal governments… My awareness of what the community in north Nashville has meant is great. And a lot of people have expressed that.”

LaTonya says that Jefferson Street’s influence touches the lives of everyone in the Mid-South and not just the local black residents of that area of Nashville. “I think there needs to be an awareness of this history,” she continues. Referencing a quote from her production assistant, she says, “People know the music and the entertainment… but that’s just background noise. What we’re trying to do is really give the complete composition of what that community was.”

Pre-dating the scope of the documentary, Jefferson Street’s story began with the area being a haven for former slaves. LaTonya says that, just like other areas in the U.S. following the Civil War, many former slaves stayed around the areas familiar to them. Later, the area became a beacon for black education, as evidenced by the founding of the notable historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) of Fisk University, Meharry Medical College, and Tennessee State University in that community. Those institutions represented the desire of black residents—directly and indirectly impacted by slavery—to better their lives.

LaTonya says she can’t pinpoint an exact cause, but that her research has shown her firsthand that residents of Jefferson Street are being displaced because of a systemic decline and de-valuing of support for the community over time.

“I think because Nashville is thriving and growing economically, and now those areas near downtown are becoming more desirable. What you see is people being displaced because of that attraction. And, because they, in many cases, don’t have those resources to either resist or push back,” she says. LaTonya adds that among the people she’s spoken to that are associated with Jefferson Street, there is a desire to keep the community’s identity intact. That desire to keep the legacy alive is part of the reason she made the documentary.

Bringing the Jefferson Street legacy into focus, the documentary takes a look at what LaTonya feels makes the area so unique. Outside of the trio of academic institutions, a cast of historical figures have worked in or visited the area. Organizations like Fisk University’s Jubilee Singers and Negro League baseball teams were known for their presence in the area. Likewise, Frederick Douglass, suffragist J. Frankie Pierce, and celebrities including boxers Joe Louis and Muhammad Ali or entertainers Ray Charles and Jimi Hendrix all occupied a space along Jefferson Street at one point in time.

Aside from the musical celebrities who have visited and performed in the area, Jefferson Street’s appetite for rhythm and blues music is a part of the genre’s story nationwide. The area is also home to the Jefferson Street Sound Museum, a facility conserving the stories and memorabilia of the sounds played in the area.

Still, despite this rich cultural and musical heritage of the area, there have been attempts to erase or at least diminish its legacy. LaTonya states that the area has faced attempts to target and displace residents, culminating in the construction of Interstate 40, which cut through that area.

“The city and the planners… did not give an exit for Jefferson Street… The exit you see now was put in later after much protest and legal fighting,” LaTonya explains. She notes that her research found over 300 homes and businesses were pushed out of Jefferson Street by the interstate’s construction. LaTonya reports that some people claim that was done intentionally because of the Civil Rights activity in the area, including the student sit-ins and marches by the students attending the Jefferson Street’s HBCUs. She offers that the Nashville sit-ins were a model that was copied by protestors during that time.

Despite the setbacks that have made life along Jefferson Street harder, LaTonya says that the people of the neighborhood make up a resilient community who’ve endured more than their fair share of hardship. She hopes to bring attention to their stories, possibly to prompt positive change to keep the area’s identity. “It will take a united effort, as well as outside… support and interest to really help stop the hemorrhaging and make sure that things are preserved,” she states.

That united effort includes the continued storytelling about the rich history and present contributions of the Jefferson Street area, with shorter documentary pieces that flesh out other parts of the story. These “extras” may add to the value the documentary will have as an educational tool for local schools wanting to understand local history. LaTonya says, “There are many people still there who are trying to make sure that history and legacy is preserved. This is not just a blighted part of town that developers and opportunists can just come in and raze to the ground to build bright, tall, new condos. There’s much more going on there.”

NPT’s Facing North: Jefferson Street, Nashville premieres on-air and online Monday, Sept. 21, at 8 p.m., with an encore broadcast Friday, Sept. 25, at 7 p.m. The documentary re-airs Friday, Sept. 25, at 7 p.m. on NPT; and Wednesday, Sept. 23, at 8 a.m.; Thursday, Sept. 24, at 1 p.m.; and Friday, Oct. 2, at 11 p.m. on NPT2. The program will be available to stream via NPT’s website. For further information about NPT’s programming, be sure to visit NPT’s website and social media.